The construction industry is one of the most male-dominated sectors in Australia. Women make up only 14% of those employed in the sector - a statistic that has changed very little in the last 20 years (see figure below). Since 2006, the sector has had the lowest levels of female representation within its workforce of any industry (including mining) (The Cost of Doing Nothing Report, 2021).

Composition of the construction workforce by occupation

Source: Frontier Economics analysis of ABS Census 2021 data

Ahead of the Government’s upcoming Economic Reform (Productivity) Roundtable we ask:

Is this the efficient outcome for the Construction industry? Or can efforts to increase female participation help improve productivity?

What is allocative efficiency?

The link between female participation and productivity or efficiency may not be immediately clear.

Productivity improvements are generally thought of as being driven by technological improvements or the uptake of new ideas and innovations. But they can also come by improvements in workforce health, allocation or management practices.

Allocative efficiency in production refers to using resources where they would be most productive. This concept can be applied when considering the impact of any barriers to female participation in the construction sector.

In a labour market with no barriers to participation, workers would be incentivised to find roles that suit their skills and interests. Individuals who have great sporting ability might pursue a tennis career, while individuals with a knack for economics could end up at Frontier Economics. Over time, workers get matched to jobs or roles in which they are most productive, resulting in an efficient allocation of labour resources. Which in turn ensures the economy’s skills and talents are used to the fullest.

But it is not clear this is happening in the construction sector.

Cultural and workplace barriers lead women who may be well suited to the construction sector to work in industries that do not best utilise their talents.

Barriers to participation in the sector

The Building Gender Equality: Victoria’s Women in Construction Strategy identified several factors that may explain the industry’s inability to attract, recruit and retain female employees. Notably, inflexible hours and work arrangements which typically extend beyond Monday to Friday, excessive hours and a lack of access to paid parental leave or return-to work provisions. These arrangements are particularly challenging for those with caring responsibilities (predominately women).

The construction industry has also long been perceived as a “boys’ club”. This perception and other cultural factors may discourage women from pursuing a career in the sector. Read "Retention over Attraction: A Review of Women’s Experiences in the Australian Construction Industry; Challenges and Solutions" and "The gendered dimensions of informal institutions in the Australian construction industry" for more information.

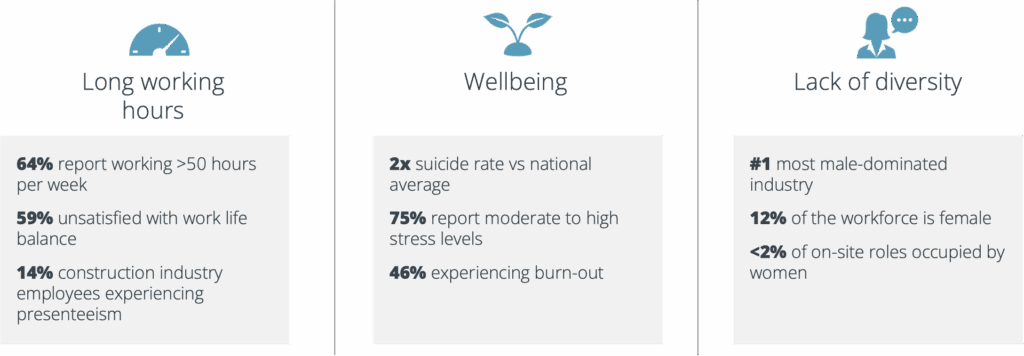

Construction Industry Statistics

Source: p7, Culture in Construction Taskforce, ‘A Culture Standard for the Construction Industry – Consultation Paper’

These barriers mean that the construction industry loses access to a large portion of the labour force. Workers who are well suited to the sector choose roles where they may be less productive, but that better suit their lifestyle or life stage.

The misallocation of workers is likely impacting on Australia’s productivity

There are good historical examples of why this matters. Consider the US labour market in 1960 where 94% of doctors and 96% of lawyers were Caucasian men compared to 63% and 61% in 2010. This was not because men were better doctors and lawyers, but because it was culturally, and in some cases, legally, unacceptable for anyone else to fill these roles. Over time, the removal of legal, structural and cultural barriers has allowed other individuals, with innate talent to make use of this talent. It has been estimated that the improved allocation of talent or occupational redistribution is responsible for of the growth in GDP per worker in the US over those 50 years.

Some may argue that work in the construction sector is inherently physical meaning men are more innately suited to working in this sector. While physicality is important for some roles this is by no means universal.

For example, in electrical trades, an interview-based study from Victoria University found that eight out of nine employers did not see women’s physical capability to be an issue for their work. More generally as technology develops, we would expect any physical barriers to diminish over time.

High turnover and low retention are costly for the industry

Parents must often choose between progressing their career in the sector or starting a family. And perhaps unsurprisingly the employee turnover rate in the construction sector is high at 9.2%, compared to 8% for the wider economy.

More flexibility in working arrangements may help the industry hold on to its skilled workforce and maximise the value gained from their past training and development (Productivity Commission, 2023). Our recent work for the Construction Industry Cultural Task force has highlighted the significance of this impact.

Some lessons for improving productivity

Existing arguments for increased gender diversity usually reference mechanisms like reduced workplace bullying, improved job satisfaction, better communication with clients, and greater rates of innovation.

Without taking away from these ideas, work practices that discourage women from working or staying in the construction sector in all likelihood create a worker-job misallocation. Fundamentally improving workplace flexibility and removing other unnecessary barriers to participation, whether real or perceived, will improve allocative efficiency in the industry and drive productivity in the economy.

Something for the attendees at the Government’s upcoming Economic Reform Roundtable to keep in mind.