At the International Institute of Communication’s Telecommunications and Media Forum, Sydney 2023 our Economist Warwick Davis joined a panel on competition issues in the sectors and commented on proposed merger reforms in Australia and the United States. He suggested that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)’s proposed reforms for processes and legal tests for merger clearance will be contentious but seem more likely to produce economic benefits than the proposed changes to merger guidelines in the United States. This note explains the reasons for his view.

Merger reform proposals are a response to increasing market concentration

Competition authorities in many parts of the world are steering the debate on mergers towards sterner enforcement. The recently released details of proposed changes to merger enforcement in Australia and the United States show that competition authorities are on quite different paths to achieve that goal.

In Australia, details of the ACCC’s proposals for merger reform, as provided to Australian Treasury in March 2023, were recently released under Freedom of Information laws.[1]

The US Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (the Agencies) issued new draft merger Guidelines[2] for comment in July 2023. As in Australia, merger guidelines do not have the status of law, but they have been influential in US court merger proceedings.

The proposed changes are different, but they are both reactions to similar concerns – perceived harms from increasing market concentration that have not been prevented by merger laws and/or enforcement practices:

There is growing evidence to support the view that Australian markets are becoming more concentrated…It is important that Australia’s merger regime is effective in preventing increases in concentration before they occur.[3]

and:

[In the United States] Empirical research…has documented rising consolidation, declining competition, and a resulting assortment of economic ills and risks.[4]

Proposed changes to US Merger Guidelines renew emphasis on market concentration

The Agencies’ draft Guidelines have undergone a substantial change in form and substance from earlier versions.[5] The draft Guidelines show the Agencies’ desire to simplify the analysis of mergers that increase concentration or occur in concentrated markets, tied where possible to legal precedent. The FTC Chair has stated the draft Guidelines do not rely on “a formalistic set of theories” but “seek to understand the practical ways that firms compete, exert control, or block rivals”, and offer several ways to analyse transactions.[6]

The draft Guidelines have 13 specific guidelines that address analytical frameworks and specific challenges relating to serial acquisitions (creeping acquisitions in Australian parlance), buyer power in labour markets, platform markets and minority interests. This includes a return (in Guideline 1) to a stricter application of the ‘rebuttal presumption’ of market concentration that was first developed by the Supreme Court in 1961[7], and the introduction (in Guideline 6) of a rebuttable presumption in the case of vertical mergers, where a market share of more than 50% is involved.[8]

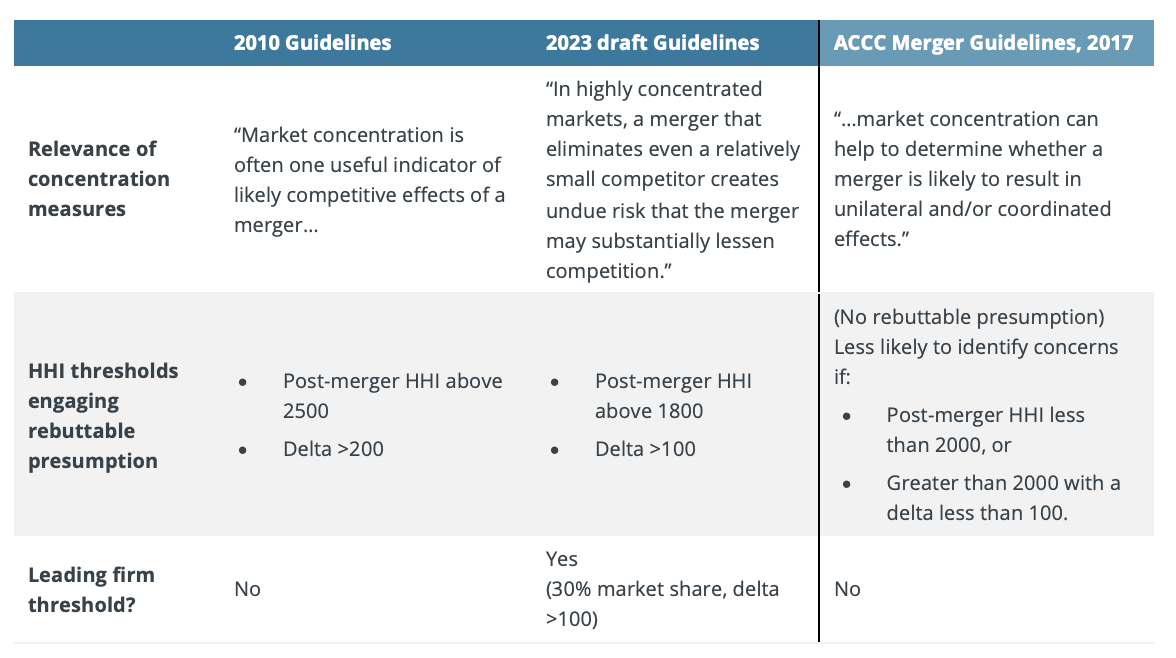

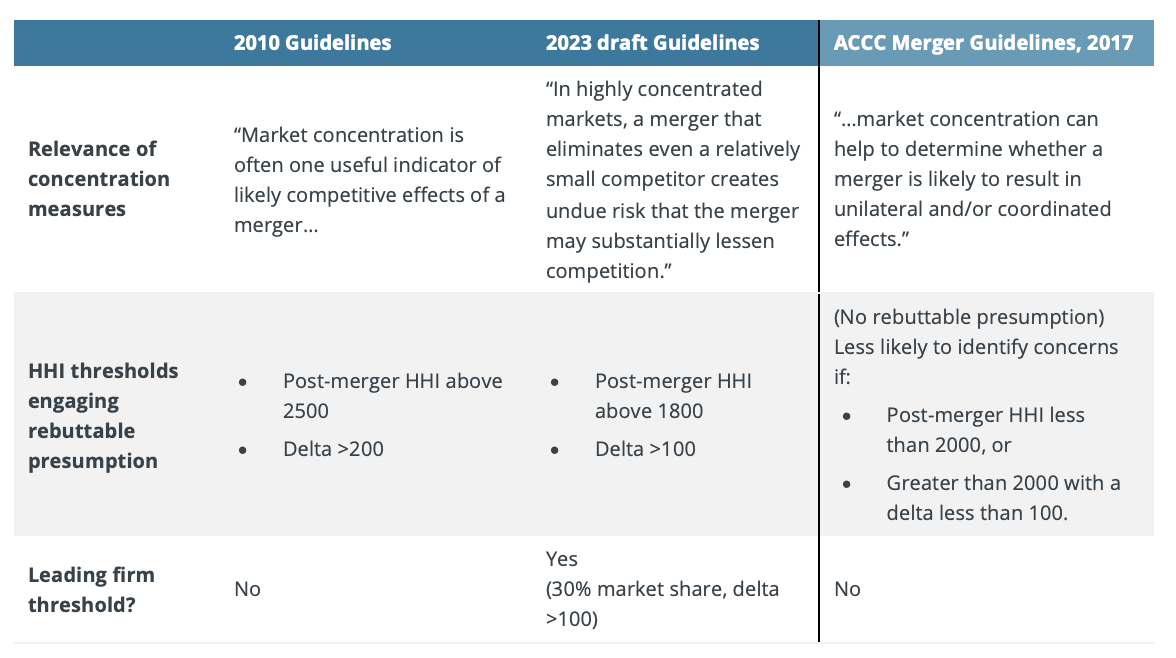

The changes from the 2010 version of the Guidelines on the significance of increasing market concentration are stark, as highlighted in Table 1. The thresholds at which the rebuttable presumption is engaged are reduced: in rough terms, a 6 to 5 merger of equally sized firms would now be subject to the rebuttable presumption while under the 2010 version it would not. For reference, the current ACCC Merger Guidelines approach (2017) is also highlighted, but these thresholds do not create rebuttable presumptions but instead provide an indication of the likelihood of concerns being raised.

Table 1: Changes in treatment of market concentration, US DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines

Source: US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines, August 19, 2010, draft Guidelines, p. 6, ACCC Merger Guidelines, 2017.

Similar problems, but different responses in merger reforms

The ACCC also has expressed concern with increasing market concentration. But the ACCC’s proposed reforms do not specifically focus on elevating market concentration to a more central role in merger analysis. Rather, the key elements of the ACCC’s reform proposals include:

- A formal merger clearance regime: large mergers could not go ahead unless a clearance was obtained from the ACCC or Tribunal.

- Changes to the merger clearance test: mergers can be blocked by the Federal Court under section 50 if they have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. The ACCC proposes that a merger would be cleared only if the ACCC (or Tribunal, on review) is satisfied that it is not likely to have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

- Revisions to the section 50 merger factors: added factors include an emphasis on creeping acquisitions and entrenching existing market power.[9]

Concentrating on the right measure of competition?

We have previously suggested that the ACCC’s proposed changes to the process by which mergers are assessed, including formal merger clearance, are worthy of serious consideration. The changes would address defects in the current informal clearance regime and adjudication processes, particularly by empowering the ACCC to be the principal decision-maker and increasing the transparency of its decisions.

On the added measures, the proposed ACCC reforms are better for not aiming directly at market concentration, albeit that concentration will remain a significant element of merger investigations. This is for two reasons:

- Since the 1970s, economists have grown more sceptical of the causal connections between market concentration, competition, and economic performance. Concentration is only one factor in competitive health, and other market structures and conduct factors can be equally or more important.[10] For example, product differentiation, which is relevant to most mergers in Australia, highlights that the identity of competitors, and the similarity of their products, can have a greater influence on the competitive effects of mergers than aggregate concentration measures.

- So much emphasis on concentration places an undue reliance on the defined markets. The definition of markets is rarely clearcut, particularly where products are differentiated, and is inevitably a matter of judgement.

Striking the right balance on the cost of errors

The ACCC’s proposed changes to the section 50 legal test are likely to have a significant impact on the chance of contentious mergers being proposed and approved. Mergers that have uncertain effects would be more likely to be blocked than under the current system.

One framework through which to view the proposed changes is whether they minimise the total costs of decision-making errors:

- from not blocking anti-competitive mergers, and

- from blocking mergers that pose no threat to competition.

Compared with the existing legal test, the ACCC’s proposed changes will reduce errors of the first kind while increasing errors of the second kind. Both kinds of errors are relevant: while errors of the first kind harm consumers directly, blocking mergers that are pro-competitive will also harm consumers.[11] Undoubtedly, the balance of errors is complex to assess and we expect further debate over whether the proposed change restores or upsets the right balance.

Other proposals to structural merger factors seem more likely to be positive. The proposals focusing on accumulation of market power address long-standing concerns about creeping acquisitions but avoid placing increased weight on market concentration thresholds. This leaves more room for nuance in the merger analysis.

A step in the right direction

The ACCC’s proposals are a serious attempt to improve the processes and outcomes of merger reviews. Although the ACCC may be concerned about market concentration, it is helpful that the ACCC has not looked to tie its proposals directly to that concern – as is being pursued in the United States. While further debate on changes to the legal test is justified, we expect the ACCC’s proposed changes have reasonable prospects of improving competition and economic welfare.

[1] https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/foi_disclosure_documents/ACCC%20FOI%20Request%20100067-2022-2023%20-%20Document%201_0.pdf (ACCC proposals)

[2] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/07/ftc-doj-seek-comment-draft-merger-guidelines

[3] ACCC proposals, pp. 4-5.

[4] Remarks of FTC Chair Lina M. Khan, Economic Club of New York, July 24, 2023, p.3.

[5] The Agencies have amended the guidelines several times since the first guidelines were released in 1968, including in 1982, 1984, 1992, 1997, 2010, and 2020.

[6] Remarks of Chair Lina M. Khan, Economic Club of New York, July 24, 2023, p.2.

[7] United States v. Philadelphia Nat. Bank, 374 US 321, 363 (1961).

[8] Draft Guidelines, p. 17: “If the foreclosure share is above 50 percent, that factor alone is a sufficient basis to conclude that the effect of the merger may be to substantially lessen competition, subject to any rebuttal evidence.”

[9] ACCC proposals, p. 11.

[10] For example, in oligopoly settings, common market features such as cost asymmetry between firms or economies of scale can reverse the standard intuition that increasing concentration reduces economic performance.

[11] The ACCC suggests that the increased costs of errors will be borne by the merger parties rather than the public. That would only be true if the merger produced no efficiencies or did not otherwise benefit competition.

Frontier Economics Pty Ltd is a member of the Frontier Economics network, and is headquartered in Australia with a subsidiary company, Frontier Economics Pte Ltd in Singapore. Our fellow network member, Frontier Economics Ltd, is headquartered in the United Kingdom. The companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered into by any one company do not impose any obligations on other companies in the network. All views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Pty Ltd.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has today released a consultation paper on NBN Co’s SAU variation. This follows NBN Co’s lodgement of the proposed variation in November 2022.

This latest proposal and consultation reflects further developments in NBN Co’s attempts to overhaul the existing SAU, accepted by the SAU in 2013, to reflect further developments in technology, increase certainty for access seekers on pricing, and move towards a more standard utility-style regulatory framework.

NBN Co’s proposed SAU variation follows a previous SAU variation, which NBN Co submitted in March and subsequently withdrew, and an extensive industry consultation process in 2021 to consider the future regulatory framework for the NBN.

NBN Co has also reinforced its preference to secure an outcome by early 2023 and allow it to develop new systems and prepare to implement a varied SAU on 1 July 2023.

NBN Co’s latest proposals are accompanied by two expert reports prepared by Frontier Economics:

The Copyright Tribunal of Singapore today released its decision in SingNet v COMPASS.

SingNet is an ISP subsidiary of SingTel. The Composers and Authors Society of Singapore (COMPASS) had been negotiating with SingNet over the cost of the licence SingNet needed to broadcast music. SingNet brought proceedings claiming that the licence fee requested by COMPASS was unreasonable. Frontier Economics was retained by lawyers for COMPASS to provide advice and to give evidence at the hearing. The Tribunal dismissed SingNet’s claim.

Frontier Economics advises clients on a range of intellectual property valuation and dispute support matters.

The Australian Government is currently implementing a mandatory news media bargaining code. This will fundamentally change the commercial relationships between digital platforms and certain news organisations. It will require that digital platforms - initially Google and Facebook - bargain with news media over remuneration for news content on Google and Facebook’s services.

In this bulletin, we consider some of the complexities of the code, and the challenges in finding the kind of bargains the Government is hunting for.

The news bargaining code will soon become law

The mandatory code follows from a lengthy, detailed ACCC Digital Platforms Inquiry and from the follow-on consultation processes by Government (Figure 1). The code’s bargaining framework is on track to become operational in March 2021.

See further details on the progress of the Government's Bill (Code).

The code is built around bargaining and compulsory arbitration provisions, but also provides for contracting “around” the code through individual negotiations and standard agreements.

Intervention is based on differences in bargaining power

The ACCC in its Inquiry recommended a code (initially voluntary) to address bargaining power imbalances between major digital platforms and media businesses. The imbalance is said to stem from these platforms being “unavoidable trading partners” for news publishers.

Figure 1: Progress of reforms on news media and digital platforms

(Download full report below for larger image)

Digital platforms use news content by linking (or allowing links) to news items on their services, including previews or snippets. This allows digital platforms to maintain the attention of their users, and so increases their ability to sell “eyeballs” to advertisers. Historically, the digital platforms had not paid the content generators in Australia (i.e. the Australian news media) for the use of these links.

The ACCC’s interpretation was that news media lacked the bargaining power to seek payment. The lack of power comes from the different consequences from news media withholding supply of news. Withholding hurts both parties, because it makes the digital platforms less useful and reduces click-throughs to news media sites. However, the argument is that withholding makes individual news media entities relatively worse off than the larger digital platforms because those platforms have a wide variety of sources for news links.

The argument then goes that this inability to seek payment has reduced news media’s ability to fund the production of news. The Government has supported the ACCC’s position - and identified it as a particular problem - because news has special public interest characteristics in a democracy.

Designated digital platforms

The responsible Minister will designate digital platforms and services to which the mandatory code applies. The stated intention is to designate Google’s search services and Facebook’s news feed service. Apple, through its News platform, is the next most obvious candidate.

The designation provisions have two main points of interest.

The first point of interest is that there is only one criterion against which platforms are to be assessed. This is whether the Minister considers there to be a significant bargaining power imbalance between Australian news businesses and the digital platform.

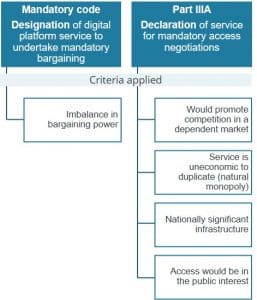

Because the bargaining code imposes compulsory participation for platforms, the bargaining code is quite different from the hotly-contested Part IIIA access regime process for the declaration of nationally-significant infrastructure services. The criteria in the Part IIA access regime (Figure 2) are challenging to satisfy, facilitating compulsory access only where declared services use a natural monopoly facility and access would promote competition in a dependent market.

The second point of interest is that there are no substantive rights of appeal on application of the provisions. Again, this is at odds with other forms of economic regulation such as Part IIIA. However, this lack of rights to appeal is – unfortunately – becoming an all too common feature of economic regulation in Australia.

Figure 2: Comparison of criteria for mandatory bargaining and mandatory access to services under Part IIIA

(Download full report below for larger image)

The designation provisions also take a different approach to that which is to be applied in regulation of digital platforms in Europe and the United Kingdom. These proposals – which are not directed at bargaining with the news media specifically – focus on designating platforms through either quantitative criteria relating to business size (EC) and/or the presence of entrenched market power (UK).

Challenges of numerating news remuneration

The proposed bargaining code requires bargaining over the supply of news content to a digital platform. The code does not require any particular payment, but provides a framework for negotiation for payments.

If parties cannot agree on a payment, it is backed by access to "final offer" arbitration. The arbitral panel must accept one of the two offers, unless it considers that the final offers are not in the public interest, in which case the arbitral panel may amend the more reasonable of the two offers.

The economic issue of suitable compensation is a particularly thorny one.

Economics tells us that voluntary exchanges create value to the buyer and seller. How the value is divided between the parties that create it is a function of their bargaining power. The price that is agreed determines how this division of value occurs.

The current system effectively has a zero price - that is, the platforms use links to news content at no charge. That sounds like the digital platforms have all the bargaining power.

However, there is no fundamental rule that the price agreed in the absence of bargaining power would always be positive. That is, a publisher might pay a platform to host a link if the platform is highly valued – publishers pay so that consumers can click through the link to the publisher's website which is then monetised via advertising, subscription or other commercial purposes.[i] It is also conceivable that platforms and news both create value for each other (Figure 3) – which leaves an arbitral panel to determine the “net” flow of value between the parties.

Figure 3: Who pays whom?

(Download full report below for larger image)

The code guides the arbitral panel “to consider the outcome of a hypothetical scenario where commercial negotiations take place in the absence of the bargaining power imbalance.” Modelling hypothetical scenarios is very complex, and in similar circumstances, price-setters typically look for benchmarks for prices.[ii] But are there any benchmarks where prices have been agreed without (a strong degree of) bargaining power?

Digital discord

Google and Facebook’s arguments against the code vary. Google has stated that it supports the principle of a code and has deployed its own news contribution model outside of the code which has signed up publishers in Australia and overseas[iii], but has three key issues with the current proposals:

- the uncertainty over the broadness and vagueness of the definition of news

- the arbitration process, which Google suggests is one sided and encourages unreasonable offers

- requirements to notify news publishers of changes to algorithms, which are not provided to other parties.

Facebook has stated that the code compels it to pay for news content in a way that is not connected to commercial reality, including encouraging ambit claims. Facebook suggests it is effectively compelled to acquire all news content at whatever price is determined.

Agreement or arbitration?

It is difficult to predict how the bargaining code is likely to perform in practice, and, in particular, how well it will achieve its main goal of encouraging commercial negotiations to increase the flow of funds to Australian news media.

There are certainly significant penalties for not bargaining in good faith – as much as 10% of annual turnover. However, as with any new law of this kind, significant uncertainties remain. For example, it appears that the code allows for compulsory price determination without actually requiring digital platforms to provide access to their platforms at all. This has raised the spectre of Google removing search functions and Facebook removing news links posted on its platforms.

The Government has remained unmoved by such possibilities, maintaining faith that bargains will be struck, and has made significant provision for those bargains to occur outside of the code itself.

In our experience, firms do not like the risks associated with (highly) uncertain arbitration outcomes. This would favour settling. On the other hand, the uncertainty in the law may favour one side thinking it can get a bargain in arbitration.

At the time of publication, the situation is by no means settled. The forthcoming weeks and months will be closely watched by digital platforms, news media and policy makers alike.

Postscripts

Update– 18/2/21

Google’s and Facebook’s activities in the last few days have revealed very different approaches to the forthcoming parliamentary assent of the mandatory news code.

Google has settled payments with most of the larger Australian news media organisations, including a global deal with News Corporation. These deals are not subject to the mandatory code, but have been struck with knowledge of the major provisions as drafted.

Facebook has elected to prevent users including news media from sharing local and international news content on its website. Facebook has again reiterated its key concerns with the code, and identified the difference between itself and Google: that Google Search is inextricably intertwined with news and publishers do not voluntarily provide their content. Facebook suggests that publishers willingly choose to post news on Facebook, as it allows them to sell more subscriptions, grow their audiences and increase advertising revenue.

In terms of Figure 3, Google appears to be accepting that it is closer to the left end– that content keeps the user on Google’s services and helps it sell advertising (platform pays publisher). Facebook sees itself as more to the right, in that it helps publishers at least as much as Facebook benefits (meaning no payment, or publisher pays platform).

The early signs are that the code has delivered on its promise of a significant shake up in the funding of news in Australia – but not necessarily delivered all of the bargains the Government was hunting.

Update – 24/2/21

The Government has now moved amendments that address some of Facebook’s concerns with the code. This includes that the Minister’s designation decision should take account of whether the platform has made a significant contribution to the sustainability of the Australian news industry; that there be a compulsory mediation process prior to arbitration; and that more notice be given of a platform designation.

In exchange for the changes to the code, Facebook will restore links to Australian news content. Facebook has committed to entering into good faith negotiations with Australian news media businesses and seeking to reach agreements to pay for content. Seven West Media became the first Australian media group to agree to a commercial arrangement with Facebook.

The effect of the changes to designation makes it more difficult for the Minister to designate a platform service. Potentially, a platform could use the existence of a number of agreements with news businesses to argue against designation where a platform is in dispute with a single news business. However, the additional designation criterion offers little in the form of a clear or quantitative threshold.

Notes:

[i] For example, ad-based content recommendation platforms Taboola and Outbrain work in this fashion.

[ii] At least in concept, similar issues of value have arisen in disputes around copyright and in retransmission of free-to-air broadcasting signals that benefit both television networks and pay TV providers. In Australia, the Australian Copyright Tribunal has made a number of determinations on the equitable remuneration that pay TV supplier Foxtel should pay to free-to-air networks for retransmission of broadcasts. The Tribunal adopts the hypothetical bargain approach but this has not led to simple or agreed methods of price determination. See Audio-Visual Copyright Society Limited v Foxtel Management Pty Limited [2012] ACopyT 1.

[iii] Google has struck agreements with smaller publishers including the Conversation and Crikey, and has announced agreement with Seven West Media on 15 February 2021. Google also recently announced an agreement with French publishers.

DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

How real options analysis improves decision making

Standard techniques used to appraise commercial and government investments often ignore the value of flexibility to adapt investment strategies as circumstances change. Misvaluation of this kind can result in suboptimal investments being chosen. This problem can be particularly acute for infrastructure projects, which typically involve large sunk costs and uncertainty over long asset lives. Real options analysis addresses this shortcoming by valuing flexibility explicitly, thereby promoting better decision-making.

Making decisions under uncertainty

The 6th of June 1944 marked the beginning of the Battle of Normandy, a decisive turning-point in World War II that led to the liberation of Western Europe. Under General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s bold plan, 160,000 Allied troops would cross the English Channel under cover of darkness, land on several beaches in Northern France and push deep into German-held territory. The Normandy landings remain the largest seaborne invasion ever recorded, and one of the most successful Allied campaigns during World War II. However, the whole endeavour was nearly scuppered by the most mundane of things: bad weather.

The landings were originally planned for the 5th of June. However, it became clear by the 4th that heavy winds and rough seas would make the audacious landings impossible. Meteorologists advising Eisenhower forecast that conditions would improve sufficiently by the 6th for the invasion to proceed. The Allied Commander wisely heeded the advice to delay, changed plans that had taken months of meticulous preparation—and the rest, as they say, is history.

Flexibility when making decisions is valuable not just in military strategy. All of us adjust our plans in response to changing circumstances and new information—whether that entails taking a different route home from the usual one to avoid traffic, or more life-changing choices, like whether to buy a house when the outlook for the property market is highly uncertain.

Commercial and public investment decisions are no exception. Businesses and governments making major investment choices often do so in the face of significant uncertainty about the future. Rarely are the investment choices completely fixed. Investment plans can often be adapted—for example, by waiting to see what happens rather than taking a decision now, or by pursuing a different investment strategy—when confronted with new information that affects the value of the investment.

Bizarrely, even though many investors do in practice change their behaviour in response to new information, the techniques typically used to value investments ignore this flexibility. For example, standard Net Present Value (NPV) analysis used in commercial investment appraisals and cost-benefit analysis (CBA) used to assess the net public benefits of government investments generally assume fixed investment plans that cannot be revised, regardless of how circumstances change.

If the flexibility to change investment strategies is valuable—and it can be materially so in many situations—then standard NPV analysis and CBA will understate the value of investments. Investors who realise this often resort to ad hoc, qualitative judgment in order to take account of the value of flexibility—usually an excellent way to make bad decisions.

Worse still, what happens if two competing investment options are being considered side-by-side, but one presents the investor with more (or different kinds of) flexibility than the other? How are those two options to be compared on a like-for-like basis? Unless the flexibility is valued quantitatively, there is every chance that the two investment opportunities will not be compared on a level playing field, and the wrong (i.e., value-destroying) investment may inadvertently be selected.

The value of flexibility: a simple example

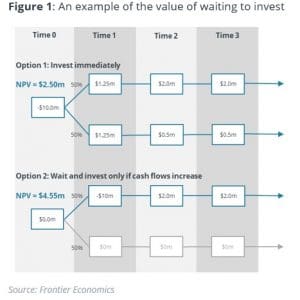

Figure 1 presents a simple example, which shows that when faced with uncertainty, flexibility to respond to new information can increase the value of an investment.

Consider two investment options available to an investor.

Under Option 1, the investor can invest at Time 0 at a cost of $10 million. The investment will provide a guaranteed cash flow of $1.25 million at Time 1. However, the cash flows at Time 2 (and thereafter) are uncertain: with equal probability they will either rise to $2 million, or fall to $0.5 million. This uncertainty resolves only at Time 1. Under Option 1, this occurs after the investment decision has been. If the investor takes Option 1, the expected NPV of the investment (at a constant discount rate of 10%) would be $2.5 million.

Note that the expected NPV represents the average outcome, given that there is a 50/50 chance of cash flows from Time 2 onwards increasing or falling significantly. If the investor is unlucky and cash flows drop, then the actual NPV of the investment would be -$6.59 million. The investment would have turned out to be a very bad one.

Under Option 2, the investor could—in recognition of uncertainty about the future—wait until Time 1 and choose to invest only if the cash flow at each point in time increases to $2 million. This would mean giving up a guaranteed cash flow of $1.25 million at Time 1. However, in exchange, the investor can avoid an outcome where the cash flow drops significantly and forever to $0.5 million, producing a loss-making investment. If the investor takes Option 2, the expected NPV of the investment would be $4.55 million—significantly higher than under Option 1, where the investment would occur immediately regardless of future uncertainty. By selecting Option 2, the worst the investor can do is avoid losses by not investing if the cash flows decline.

The difference in the NPVs under Options 1 and 2, $2.05 million, represents the economic value of flexibility (the ‘option value’) to change the investment strategy in response to new information.

Real options analysis

Real options analysis (ROA) is a technique that allows the systematic quantification of the economic value of flexible decision-making. Unlike standard NPV analysis or CBA, ROA recognises that investors can alter the way a project is rolled out as circumstances change and calculates the value of the project under different possible investment strategies rather than a single, fixed strategy.

Examples of flexibility in decision-making that ROA can account for include the options to:

- delay investment until uncertainty is resolved;

- roll the investment out sequentially to see how each stage pans out before progressing to the next;

- change course, expand or downsize as new opportunities and risks crystallise; and

- abandon/exit if conditions turn unfavourable.

ROA has two main advantages over standard NPV analysis and CBA:

- Firstly, ROA can provide a more accurate valuation of potential projects by accounting explicitly for the fact that the investment strategy can be modified in response to changing circumstances. This removes the need to account for the value of flexibility qualitatively and reduces the risk of selecting a suboptimal investment.

- Secondly, ROA allows the identification of the value-maximising investment strategy. This is because ROA involves mapping out all the feasible future pathways for an investment, in response to changing circumstances, and then finds the pathway that would maximise the value of the investment. This value-maximising pathway represents the optimal investment strategy, given the present understanding of how the future might unfold.

When is flexibility valuable?

A key insight from the ROA literature is that the value of flexibility can be particularly large if:

- There is significant uncertainty over the future payoffs (e.g., cash flows, social costs/benefits) from the investment. If future outcomes are easy to anticipate, then planning would be straightforward, and there would be little need to modify the investment strategy over time. In this context, uncertainty refers to the variability of possible future outcomes. The larger the range of possible future outcomes, the greater the uncertainty faced by investors, and the greater will be the value of flexibility.

- The investment decision is irreversible (or is very costly to reverse). If investment decisions can be undone easily, then investors could simply withdraw from the investment without incurring a significant loss. However, if the cost of the investment is sunk once made, then investors cannot exit without suffering a loss. Generally, the larger the sunk cost involved, the greater will be the value of flexibility.

This means ROA can be particularly useful when valuing infrastructure investments—such as: roads, rail lines, ports, airports, water networks, desalination plants, water recycling plants, telecommunications networks, mining and exploration assets, gas pipelines, electricity grids and power stations.

This is because infrastructure investments tend to be long-lived (so economic conditions can change materially over the life of such assets), and typically involve billions in sunk costs.

The NBN: an application of ROA

With a forecast peak funding requirement of $51 billion, the National Broadband Network (NBN) represents the largest infrastructure project ever undertaken in Australia.

Given the size of the project, it is astonishing that the Rudd Labor government, which pledged to deliver the NBN, refused to conduct a CBA to assess its merits. Indeed, the Federal Communications Minister at the time argued that the benefits of the NBN to Australia were self-evident, and that conducting a CBA would be a “waste of time, waste of effort, waste of money.”

The most contentious aspect of Labor’s NBN plan was a commitment to deliver fibre to the premises to 93% of the population with broadband speeds of up to 100 megabits per second. The ambitious choice to build fibre to the premises was intended to deliver a network with sufficient capacity to last for generations, but also involved the highest construction costs.

The decision to roll out fibre to the premises was particularly controversial because it was unclear in 2009, when the plan was first announced, that there would be sufficient future demand to justify the broadband speeds and build costs associated with a fibre to the premises network. Whether fibre to the premises would be truly worthwhile depended on what sort of applications would emerge, and how consumers would choose to use broadband services, in future. However, the government of the day pressed on with its plans for a “Rolls-Royce” NBN as though such speeds would definitely be required, regardless of the uncertainty over future demand. No account was taken of the option to delay or to build gradually.

When Labor lost the 2013 general election, the incoming Coalition government commissioned a CBA of the project. That study assessed the net benefits to taxpayers of three options for rolling out the NBN. It concluded that, against the base case scenario of halting the project immediately:

- A rollout using hybrid-fibre coaxial and fibre to the node to 93% of premises, without any government subsidy, would provide the highest incremental net benefit of $24 billion;

- A multi-technology mix rollout using a combination of fibre to the premises, fibre to the node, hybrid-fibre coaxial, fixed wireless and satellite solutions would deliver incremental net benefits of approximately $18 billion; and

- A fibre to the premises rollout to 93% of premises (per the original Labor plan) would deliver incremental net benefits of less than $2 billion.

The study suggested that Labor had picked the worst of all rollout options.

A commendable aspect of the CBA—which made it stand out compared to most other government CBAs—was that it made some effort to account for optionality. The CBA recognised that a key uncertainty was the extent of future growth in demand for high-speed broadband. The study concluded that whilst a multi-technology mix rollout would offer slower speeds than a fibre to the premises rollout, it would allow the NBN to be upgraded at a later date, if demand turned out to be higher than anticipated.

The authors of the CBA modelled the net benefits of having the ability to upgrade later if required, under a multi-technology mix rollout, instead of building full fibre to the premises capability upfront. Figure 2 presents the value of the multi-technology mix rollout over and above the fibre to the premises rollout if:

- the network was never upgraded, even if consumers’ willingness to pay for high-speed broadband were to increase over time (the black curve); and

- the network was upgraded in response to growing willingness to pay (the dashed red curve).

This analysis demonstrated two important things:

- Firstly, once the flexibility to upgrade the network in response to demand growth had been accounted for, the multi-technology mix rollout looked unambiguously better than the fibre to the premises option. Had this flexibility been ignored, a multi-technology mix build would have appeared a worse option than fibre to the premises under a high willingness to pay scenario (i.e., the black curve eventually drops below an NPV of $0), when in fact it was not.

- Secondly, it is possible to extend standard CBA using ROA to quantify the value of flexibility. The red curve represents the value to be gained from following the most flexible investment strategy. This allows decision-makers to understand in dollar terms what society would be giving up if a less flexible strategy (i.e., a fibre to the premises rollout) were adopted instead, given uncertainty about the future.

Based on these results, the CBA concluded that:

Overall the [multi-technology mix ] MTM scenario has significantly greater option value than the [fibre to the premises] FTTP scenario. The MTM scenario leaves more options for the future open because it avoids high up‐front costs while still allowing the capture of benefits if, and when, they emerge. It is, in that sense, far more ‘future proof’ in economic terms: should future demand grow more slowly than expected, it avoids the high sunk costs of having deployed FTTP. On the other hand, should future demand grow more rapidly than expected, the rapid deployment of the MTM scenario allows more of that growth to be secured early on, with scope to then upgrade to ensure the network can support very high speeds once demand reaches those levels.

Making us better off

John Maynard Keynes is often credited with saying “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?” In fact, the actual source of this quote was not Keynes, but Paul Samuelson, another famous economist.

Regardless of who actually said the words, the sentiment behind them makes intuitive sense to most of us. We do not go through life following a perfect linear path, regardless of what life throws at us. We adapt our plans as circumstances change because doing so makes us better off.

Commercial and government investment decisions are much the same. Yet, standard NPV analysis and CBAs used to appraise such investments typically ignore the value that can be gained from changing the investment strategy in response to new information. This can result in the value of investments—particularly those that are long-lived, exposed to significant future uncertainty and involving large sunk costs—being mis-estimated. This, in turn, can lead to suboptimal investments being selected, at significant cost to shareholders or taxpayers.

ROA addresses this problem by quantifying explicitly the value of flexibility, and allowing identification of optimal investment strategies, thereby improving decision-making.

To download this publication in full (including references), click the button below.DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

The Competition Commission of India (CCI) recently unconditionally cleared Facebook's acquisition of a 9.99% stake in Jio Platforms through its subsidiary Jaadhu Holdings LLC. In addition to this investment, the acquisition involved a strategic tie-up whereby JioMart would use WhatsApp as one of the communication channels for its retail business.

The CCI examined many theories of harm. In relation to horizontal concerns, the CCI examined overlaps in consumer communications apps and online advertising. In relation to vertical concerns, the CCI explored leveraging issues in the e-commerce space and electronic payment mechanisms, and analysed whether the parties would have an incentive to deviate from net neutrality. The CCI also considered whether there would be any adverse effects resulting from data sharing between the Parties. The CCI concluded that the combination was not likely to have any appreciable adverse effect on competition in India on any of the above theories.

A team from Frontier Economics (Europe) and Frontier Economics (Asia-Pacific) advised Facebook on the economic aspects of the competition clearance. The team was led by Director David Parker, with Martin Duckworth, Carlotta Bonsignori, Eleanor Monaghan and Monica Gambarin from Frontier Economics (Europe) and Warwick Davis from Frontier Economics (Asia-Pacific).

The Competition and Consumer Commission of Singapore (“CCCS”) has issued its findings and recommendations for its market study on e-commerce platforms. The market study focused on gaining an in-depth understanding of e-commerce platforms that compete (or potentially compete) across multiple market segments offering distinct products and/or services.

The study also analysed potential competition and consumer issues which may arise from the proliferation of such e-commerce platforms.

Frontier Economics (Asia Pacific) was appointed to undertake a consultancy study for the CCCS. This study formed a key input for the CCCS’s findings and conclusions. Our work consisted of a consumer survey, focused interviews and an economic analysis of the emerging literature on digital platforms and its application to e-commerce activities.

While no specific competition problems were identified in the course of the market study, further analysis of theories of competitive harm relating to competition in multiple markets was undertaken. The CCCS consequently elected to update some of its key guidance documents, including competition guidelines relating to market definition, mergers and abuse of a dominant position.

With respect to consumer protections, our analysis highlighted that many e-commerce platforms had developed consumer trust, as this was a critical part of platform success. However, the Frontier Economics consumer survey did highlight concerns with unfair consumer practices in online markets, and the CCCS has proposed further information dissemination and commitments from key e-commerce platforms to better inform sellers on their platforms.

The full report is available at: https://www.cccs.gov.sg/resources/publications/market-studies

The GCR Live Interactive 2020 conference was held in Singapore and virtually on 4-5 September, 2020.

Philip Williams participated in a panel discussion, "When antitrust, consumer protection and data protection laws collide” and these notes were presented as part of the session.

DOWNLOAD NOTES

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission has opened up consultation on its draft bargaining code between digital platforms and news media.

The bargaining code arises from the digital platforms inquiry, completed in 2019, and looks to address issues of power between the two groups in negotiating payments for content. In particular, the digital platforms considered are Google and Facebook, while the news media covers all media organisations providing news to Australian services.

The concepts paper sets out 59 questions it is seeking input on, with submissions required by 5 June (a brief 14 working days consultation window). The consultation questions pose range from the definition of news to be covered under the code, to issues around bargaining, use of user data, and the way the digital platforms algorithms operate.

The ACCC anticipates it will release a draft mandatory code for public consultation in late July 2020. With digital platforms attracting attention from regulators around the world, it is likely that Australia’s response will be of interest as one of the first regulators to take action in this particular area.

Frontier Economics regularly advises clients on issues in telecommunications, media and digital platforms.

For more information, contact us.

Four years ago, then Federal Senator Nick Xenophon and Frontier Economics jointly made the case in the mainstream press for the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) to end the fixation with inflation targeting and instead move to targeting nominal GDP. A Frontier Economics bulletin at the time explained nominal GDP targeting in more detail. Instead, the RBA continued on with its single minded approach. Not only did the RBA undershoot its inflation target over the ensuing period, it also presided over rising unemployment in the 12 months prior to the country being devastated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Australia could have avoided much economic pain had it shifted its position on inflation targeting years ago. This shift away from inflation targeting is now being supported by others in a recent op-ed in the Australian Financial Review. Now is the time for the RBA to move on.