The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) is continuing its inquiry into the electricity supply market within the National Electricity Market (NEM). As part of their latest Electricity Market Inquiry Report, Frontier Economics was asked to explore the evolving contracts market in this sector. This is particularly important given the rapid push towards renewable energy and associated changes in government policy.

Utilising interviews with key industry stakeholders, and our own analysis, the report is focused on how the electricity hedging market might evolve over the next 10-15 years. This is a period the electricity market will be in transition. A particular emphasis is placed on how retailers, especially those without generation assets, will be able to manage risk.

Key findings: Electricity risk management and market evolution

The report outlines several key findings.

Firstly, an efficient hedging market is crucial for risk management, reducing energy costs, and ensuring a competitive retail market that benefits consumers. There are several tools that retailers can use to manage the risk of fixed consumer prices with the more volatile wholesale electricity market. These tools include financial contracting, vertical integration, or demand response strategies.

Secondly, the energy market transition, driven by government policy for a low carbon economy, is affecting electricity markets in complex ways. It is expected to reduce dispatchable capacity, such as thermal generation. The replacement to this will be renewable generation, where most of this output is dependent on whether conditions. This impacts on the ability for this supply to offer the firm base load swap contracts that have traditionally been sold by baseload coalfired generators, or cap contracts sold by gas peaking plants.

We have also identified several potential challenges for retailer risk management evolving from the transition to more intermittent generation. These include:

- Increased spot price volatility, which could challenge the ability for independent retailers to manage risk.

- Traditional contracts and futures may not meet the evolving risk profile of retailers, with a likelihood that more bespoke contracting will become increasingly necessary. This may have implications for trading exchanges, such as the ASX, to offer products that retailers need.

- The availability of financially firm contracts is expected to reduce, making it harder for retailers to rely on contracting to source efficiently priced financially firm contracts. Drivers for this include the retirement of dispatchable generation sources, but also the potential that government supported generators have a reduced incentive to make contracts available to the market.

- If vertical integration becomes necessary to effectively manage risk, this may foreclose on opportunities for smaller new entrant retailers.

Strategies and options to assist future retailer risk management

Our report sets out several strategies for the ACCC and Government to explore to improve outcomes for retailers in the future given the expected challenges they will face. These are:

- Given governments currently fund the majority of new supply technologies in one form or another, we consider the ACCC, and the Government should identify if there are ways that these government funded generation/storage projects could be used to support qualifying small retailers with access to a quantity of hedges.

- The Government may wish to also investigate underwriting new products on futures exchanges. The intent being to support the development and availability of these products until sufficient liquidity emerges.

Importantly, our report advocates against market interventions, such as market design changes, to manage risk for retailers. Reducing risk through market mechanisms, such as reducing the market price cap, would likely reduce the incentive for retailers to contract, and in doing so, reduce the incentive for new investment in essential dispatchable capacity.

Read further by downloading the report below, or on the ACCC website. The ACCC’s Electricity Market Enquiry can be found here.

More information about our work in the energy and renewables sector is found here.

DOWNLOAD REPORT

A report we produced in 2022 has been unjustly discredited recently in regard to the Murray-Darling Basin Plan and Water Amendment (Restoring Our Rivers) Bill 2023. Below we clarify the report’s use and findings and discuss the concerns of parties opposing the report. To read the full report, please download it below.

The “Social and economic impacts of Basin Plan water recovery in Victoria 2022” report was produced for the Victorian State Government in 2022. We analysed the social and economic issues associated with water recovery for the environment in Victoria, under the Murray Darling Basin Plan. Our report provided a valuable evidence base to support robust decision-making on Basin Plan issues.

Our scope was to build on and update the analysis undertaken for our 2017 socio-economic assessment report. The report explains the impacts being felt by communities in Northern Victoria in the 2022 context of water recovery for the environment under the Basin Plan.

Future impacts of the Basin Plan

One (of the thirteen) chapters considers the possible future impacts of the Basin Plan. The intent of this analysis was not to undertake detailed economic modelling to estimate the impact of further buybacks. Rather, we provide an indication of what is ‘at risk’ — in terms of the value of economic production and employment that is currently supported by the volumes of entitlements that could be recovered if the Commonwealth use buybacks to complete Basin Plan targets, for example the additional 450 GL.

The report does not advocate for, or against, buybacks or alternative forms of water recovery.

It documents the financial costs and socio-economic issues around each water recovery approach. It does seek to put into context the socio-economic value of water for agriculture with the aim of making government cognisant of the consequences removing this water through buybacks could have, so this can be considered when making decisions about water recovery and the support that would be needed to mitigate these impacts.

Produced with updated available data

Our report also brought significant new information to light, securing data from the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW) regarding the type of infrastructure recovery (separating out on-farm and off-farm) that had previously not been released.

Our work also secured data from the Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder (CEWH) regarding their holdings and behaviour that had not been previously made available.

Academic judgement on the water report

We note that the Murray-Darling Basin Authority (MDBA) commissioned a team from the University of Adelaide to conduct a literature review of 106 economic Murray-Darling Basin studies that are assessed and rated on a measure of ‘quality’ adapted from medical literature. This approach to assessment is not fit-for-purpose, for the range of studies considered.

Of the 65 studies that were deemed to relate to the influences of water recovery programs on economic outcomes (this report being one of them), 18 of the 28 applied studies are rated low-quality, with 10 of the 11 studies using descriptive statistics being rated low-quality. In fact, the review raises concerns with all the significant reviews in the area.

The University of Adelaide reports that “The bulk of the large-scale reviews to date (e.g., EBC et al., 2011 [appointed by MDBA to consider community impact]; RMCG, 2016; Sefton et al., 2020 [which was an independent panel appointed DCCEEW]; Productivity Commission, 2018; Wentworth Group of Concerned Scientists, 2017; KPMG, 2016; 2018; TC&A & Frontier Economics, 2017; Frontier Economics & TC&A, 2022) have not managed to identify a causal relationship between water recovery and economic outcomes.”

Furthermore, of the studies considered by the University of Adelaide team, many are not contemporary — suggesting that MDBA and DCCEEW need more evidence to support current policymaking.

At Frontier Economics, we peer-review every report with a robust methodology built over our 25 years of economic consulting experience. Academic standard-peer reviews are not practical or common-practice in real-world industry cases, and using this basis to question the quality is, in our opinion, incorrectly measured.

We invite any enquiries on this matter via contact@frontier-economics.com.au

DOWNLOAD REPORT

We were recently asked by the Nature Conservation Council of NSW (NCC) to examine the financial and budgetary drivers behind the Victorian Government’s decision to accelerate the closure of its public native forest logging (NFL) business – and how comparable these drivers are in New South Wales and Tasmania.

While the native forest logging businesses in NSW (Forestry Corporation of NSW - FCNSW) and Tasmania (Sustainable Timber Tasmania - STT) have not reached the same level of operational crisis and loss of keystone customers as Victoria, they share the fact that they have been a financial drag on taxpayers over a very long period. FCNSW’s hardwood division has a long history of poor financial returns and lost $30 million in the last two years. STT has also incurred operating cash losses over long periods.

Our previous analysis “Comparing the value of alternative uses of native forests in Southern NSW” also shows that this unprofitable business also comes at a significant opportunity cost to the community. This is in terms of the loss of alternative higher valued uses of the standing forest, and the loss of environmental services.

The poor financial position and budgetary burden posed by the publicly-owned NFL business is intensifying. Factors include the reducing log supply, increasing costs of production, and the increasing competition from alternative wood products that have dramatically reduced demand, including for structural timber from native forests.

It is time to stem the cost to the community posed by the industry and to plan for an orderly exit from NFL.

Additionally, the facts show that this would not materially disrupt downstream markets or increase illegally logged supply.

Wood production by the NFL industry has already fallen by 60% since the early 2000s, so it is possible to see what the likely impacts will be. The data suggests the markets for sawn wood products have substantially switched to softwood timber and wood-based panels. The decline in Australian native woodchip supply has largely been filled with plantation woodchips, particularly from Vietnam.

View the full report commissioned by Nature Conservation Council of New South Wales below.

DOWNLOAD REPORT

Whilst road pricing has been a hot topic in recent months in various states across Australia, the evolution of charging commuters for roads across Australia’s has been a long series of developments. With many challenges to defining how to charge commuters – including competing priorities and governance, and new technology such as EV’s, we unpack this topic below.

The challenges to tackling road pricing

Road pricing has made its way into the news recently for a number of different reasons.

Firstly, in 2021 the Victorian government introduced the Zero and Low Emission Vehicle (ZLEV) charge which levied electrical vehicle owners 2.8c for each kilometre they travelled. The intent was to charge EV users for the costs they impose on Victoria’s road network.

However, in October the High Court of Australia ruled the charge invalid, as it amounted to an excise duty, which under the Constitution, can only be levied by the Commonwealth.

Secondly, in the last year the NSW Government also announced the Independent Toll Review. This has come about because of emerging public concerns about the affordability of current tolls on Sydney motorways, particularly given the rising cost of living. Concerns have been accentuated by the inequities in tolling, whereby some motorists on their daily commute face quite significant charges, while other motorists in Sydney, pay very little.

The Independent Review has released a discussion paper which considers the efficiency and fairness of existing tolling arrangements that are set out in PPP contracts with road concessionaires.

The challenges posed by toll roads are merely a subset of the broader issues in road user charging. Whilst governments think that users should pay more directly for roads, developing a comprehensive set of road prices that applies across Australia’s road network is challenging.

Frontier Economics’ has been providing economic consulting advice in the transport sector – and on the development of road user charges – for many years. Here, we unpack the challenges of road pricing and discuss a possible path forward.

Why is pricing road use challenging?

Our Local, State and Federal governments are entering into a challenging space when it comes to the pricing roads. There are multiple reasons why pricing road use is challenging:

Firstly, there are multiple objectives to consider when pricing roads which are sometimes conflicting. Road charges can:

- Fund the development or expansion of a new motorway – as is the case with tolls.

- Be used to recover the ongoing costs of maintaining or operating the road network more generally – by accounting for the wear and tear vehicles impose on the road pavement, or

- Help manage congestion and reduce emissions – by encouraging better decision making when it comes to reducing vehicle use; to limit these third-party costs.

The second reason is that we have Local, State and Federal Government roads. This creates challenges because you immediately have multiple governments involved, and we have motorists travelling, potentially in one trip, on multiple roads that are owned by different governments. The charging arrangements for that entire network therefore becomes far more complicated.

The final layer to this is that is that different governments have different powers in respect to vehicles, vehicle use and charging. The Federal Government has responsibility for the importation and design of new vehicles, and the power to levy the fuel excise, which is often argued to be the main mechanism for implicitly funding the road networks. The State Governments are far more confined in their ability to levy state-based road charges, however, they are in charge of things like registration. So, this limits the ability for any one government to create a comprehensive charging structure on its own.

Electric Vehicles (EV) and road charges

It’s necessary for all governments to consider a reformed approach to road pricing now, because of the emergence of Electric Vehicles (EVs) – who don’t pay the fuel excise. And currently the main mechanism used to implicitly fund road development is this fuel excise. This funding is expected reduce over time, as more motorists take up EVs. Essentially, motorists will be using less fuel, and as we use less fuel, this funding source will disappear.

The time to deal with this is now. Solving this problem means moving away from current arrangements which is challenging. States, such as Victoria, have tried to go it alone by implementing road use charges for EV. But this approach has been struck down in the High Court Challenge. So, you can see states acting on their own isn’t really a great option.

What can be done to create fairer and more efficient road pricing

The first step is to acknowledge that road pricing is an issue across governments and one that might benefit from intergovernmental co-operation. An intergovernmental agreement could be developed, that sets out:

- Principles for pricing – what governments are hoping to achieve with different road use charges to deal with the problem of multiple objectives, and

- The role of different governments in this charging space. So, we don’t get competing actions – which tends to happen in part because different governments are all not empowered to act on their own.

Some pricing improvements for heavy vehicles have already been achieved. It’s been a slow process with incremental improvements but there is no reason why that process, which we have been heavily involved for the last 15 years with can’t be expanded.

Given the outcomes of the High Court Case, governments need to work together on this emerging issue, and a better, intergovernmental, solution is required if we are to create road charges that are more efficient and fair for all motorists across Australia.

Frontier Economics was an independent advisor to AustralianSuper, for Brookfield and EIG's Origin Energy takeover scheme. Our role was to review the assumptions used in the Independent Expert’s Report (IER) in Origin’s Scheme Booklet.

Using robust economic analysis and long-standing expertise in the energy sector, our advisors, engaged by AustralianSuper - a long-term shareholder in Origin - found that the assumptions used in the IER to derive a business valuation are unrealistically low.

We refer all enquires in regards to this takeover bid, and our economic advice on this matter, to AustralianSuper.

A copy of the full media release from AustralianSuper can be downloaded below.

DOWNLOAD PRESS RELEASE

Frontier Economics' Tim McNamara, Mike Woolston and Dinesh Kumareswaran were commissioned by the Water Services Association of Australia (WSAA) to produce the report Understanding Efficiency to explain in "plain English" the concepts of economic efficiency and how they apply to the water sector. The report also illustrates what efficiency looks like under different scenarios using examples from the water sector and detailed case studies. Below is the Executive Summary of the report.

About this report

The aim of this report is to explain in ‘plain English’ the concepts of efficiency and how these are utilised within businesses, by economic regulators and others to assess service and expenditure proposals in pricing submissions and business cases.

Efficiency in the urban water sector

It is important for businesses to be able to understand and demonstrate efficiency, not just to get approval of pricing submissions from regulators – but also to demonstrate they are providing value for money to customers, owners, and other stakeholders.

Common or dictionary definitions of ‘efficiency’ tend to focus on the relationship between inputs and outputs of producing a good or service, but this narrow interpretation may lead to misconceptions. Minimising costs may not necessarily be consistent with providing customers’ desired service levels, maintenance and investment in asset capability and supply resilience, or delivering broader outcomes which are desired by customers or society.

Rather, economic efficiency can be seen as synonymous with value for money - providing the services customers want at the lowest long-term cost. The regulatory frameworks applied by most economic regulators do provide for broader ’value for money’ outcomes in assessing efficiency.

Some common misconceptions about efficiency

There are a number of common misconceptions about demonstrating efficiency in the urban water sector. These related misconceptions include:

- Efficiency means prices need to be flat or declining

- Efficiency is about cutting costs to the minimum

- Efficiency is incurring lowest possible costs over the upcoming determination period

- Efficiency means providing services at the lowest possible standards consistent with regulatory and other obligations

- Efficiency is about deferring new investment as long as possible and running assets to fail

- Efficiency means minimising costs even if this leads to higher risks

- Efficiency means neutralising the impact of other drivers of expenditure (e.g. growth) so prices remain constant overall without having to disaggregate the drivers

- Efficiency means demonstrating on a once-off basis that a business is efficient relative to the industry standard.

A common thread underlying these misconceptions is that ‘efficiency’ is synonymous with cost minimisation. Not only is cost minimisation in itself not an appropriate objective - but it is not an appropriate interpretation of what it means to be ‘efficient’.

Minimising costs may not necessarily be consistent with:

- providing services at the level customers want

- maintaining and investing in asset capability and supply resilience

- delivering broader outcomes which are desired by customers or society.

How is efficiency measured and demonstrated?

While how best to demonstrate efficiency may depend on the audience, fundamentally it is about demonstrating that a proposal is in the long-term interests of customers.

The overarching approach of economic regulators in determining efficient levels of expenditure for regulated urban water businesses, which they then allow to be recovered in regulated prices, typically involves:

- Establishing the services to be provided to meet regulatory and other obligations and customers' preferences

- Establishing the minimum expenditure needed to efficiently deliver these services

- Setting prices which are forecast to enable the business to recover the total expenditure which the regulator has deemed to be 'prudent and efficient'.

Typically regulators adopt a ‘prudency and efficiency test’ to provide assurance that the businesses are (1) doing the right things; and (2) doing those things as efficiently as possible.

Regulators typically assess the prudency and efficiency of operating and capital expenditure individually, as well as the trade-off between these two types of expenditures:

- While both detailed ‘bottom up’ assessments of various operating expenditure items and broader ‘top down’ approaches which focus on broad categories of expenditure have been applied by regulators, the latter (particularly the base-step-trend approach) is becoming increasingly widespread.

- Approaches to assessing the efficiency of capital expenditure typically examine the business' capital governance frameworks, policies and procedures, and review a sample of the business's proposed capital expenditure projects. This generally requires reference to an identified need or cost driver, evidence that the business has considered alternate solutions including non-network solutions, and that the cost of the defined scope and standard of works is consistent with conditions prevailing in the relevant markets.

What lessons does recent regulatory experience provide?

We examined a number of recent regulatory reviews and decisions by state economic regulators. This provided a number of key insights and lessons that can be drawn upon for future periods.

- The Base Step Trend methodology is being adopted by a number of water regulators

- Capital projects exposed to uncertainty have the potential to be deferred to future periods

- Willingness to pay studies are helpful but should not be used in isolation to justify expenditure

- Consultation and analysis is required to demonstrate the prudency of projects

- The introduction of new services needs to predominately benefit customers

- Capital expenditure proposals should be supported by robust business cases

- Regulators often require alternative options to providing the service to be considered.

Guidance for demonstrating efficiency

We have identified some overarching guiding principles that should be adopted to demonstrate the efficiency of expenditure proposals regardless of the context in which efficiency is being measured or demonstrated:

- Adopt a business case (or cost-benefit analysis) approach to all expenditure proposals

- Focus on the long-term interests of customers, considering factors including operating and capital expenditure trade-offs and the impact on service standards over time and supported by Net Present Value NPV (analysis)

- Consider both prudency and efficiency of expenditure, including how cost proposals incorporate efficiency targets and continuing efficiencies (as would occur in a competitive market)

- Explain trends in operating and capital expenditure and key drivers of these trends

- Develop a narrative that explains the link between expenditure and outcomes for customers

- Conduct analysis that is proportionate to the size and impact of the potential expenditure.

However, there is no single methodology or technique that is appropriate to use in all circumstances to measure and demonstrate efficiency. The appropriate approach may vary depending on factors such as the nature of the:

- expenditure (i.e. operating vs capital expenditure or large ‘step’ in operating expenditure)

- activity (discretionary vs non-discretionary expenditure).

Table 1. Approach to demonstrating efficiency - a guide

| Step |

Type of expenditure |

Evidence/

data required |

Techniques |

Example |

| Outline why the spending is in the long-term interest of customers |

All |

Link spending to specific outcomes for customers in terms of services and prices over the long term

Clear ‘golden thread’ narrative |

Investment Logic Mapping |

See section 4.2 and 5.5 |

| Prudency: Link spending to non-discretionary obligation |

Non-discretionary

opex & capex |

Identify key drivers including relevant legislative or regulatory obligations |

Understanding of non-discretionary service (and related) outcomes, including their timing |

Central Coast Council (section 3.3.3) |

| Prudency: Demonstrate that customers want the proposed service/level or outcome |

Discretionary opex & capex |

Customer feedback |

Surveys, customer forums |

Case study 2 |

| Prudency: Demonstrate that customers are willing to pay for this service |

Discretionary opex & capex |

WTP studies |

Choice modelling |

Case study 2 |

| Analyse a range of options to produce the desired outcome |

All |

List of alternative options including capital vs recurrent solutions – ideally in business case |

Cost-benefit analysis |

Case study 3 |

| Identify a preferred option |

All |

Business case or similar |

Cost-benefit analysis (benefit -cost ratio, NPV etc) |

Case study 3 |

| Undertake sensitivity analysis to demonstrate the preferred option is robust |

Capex/major opex step change |

Business case or similar (preferred option is superior under a range of assumptions/scenarios) |

Sensitivity analysis

Real options analysis

Scenario analysis |

Case study 3, Sydney Water resilience expenditure (section 3.6.3) |

| Ensure/demonstrate the preferred option/proposed services will be delivered at the lowest cost |

Opex |

Historical expenditure

Productivity growth (continuing efficiency) forecasts

Market-tested estimates |

Base-step-trend

Benchmarking

|

Case study 1 |

| Ensure/demonstrate the preferred option/proposed services will be delivered at the lowest cost |

Capex

Step jump in opex |

Robust procurement process (e.g. market-testing or similar)

Detailed approach to managing delivery of project and associated risks

Proposed expenditure is within long-term context & strategy

Consideration of scope for application of continuing efficiency factor |

Business case methodology |

Powercor ICT investment (section 3.4.3) |

| Benefits realisation (ex pt) |

All |

Ex post assessment of benefits and costs |

Post project review |

See section 2.2 |

DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

Frontier Economics' Stephen Gray was commissioned by Vector to assess whether the draft Input Methodology decision by the New Zealand Commerce Commission will help or hinder the investment that’s needed to decarbonise the economy. The New Zealand Commerce Commission is currently developing a final decision over the key regulatory principles that bind the way electricity networks in Aotearoa New Zealand can operate and invest for the next seven years, and possibly longer (the Input Methodologies, or IMs).

In this video below, Stephen shares his view on how the IMs could support the network investments needed to deliver New Zealand’s energy transition to net zero by 2050.

Electrification is at the core of New Zealand’s decarbonisation strategy, and this will require extensive investment in transmission and distribution networks over a short period of time. Indeed, it will be impossible for New Zealand to meet its decarbonisation commitments without this extensive network investment.

Moreover, there is widespread agreement that investment in electricity networks today will secure long-term benefits for consumers. So it is important that New Zealand’s regulatory framework helps to facilitate the network investment that is required. However, there is a real risk that the current regulatory framework will, in fact, hinder major network investment projects.

The key problem is that the regulatory cash flows tend to be back-ended, creating a risk that the cash flows in the early years of a project’s life are not sufficient to support the credit rating and gearing that the regulator has assumed. Where this happens, a project is not commercially viable and does not proceed. And, of course, no consumers receive any benefit from a project that does not proceed.

Our analysis found the draft Input Methodologies do not contain the sort of ‘financeability’ test that regulators in other markets employ. Nor do they provide potential investors with certainty about how a financeability issue would be addressed if it was identified.

A process to ensure that the regulatory cash flows are sufficient to support the credit rating and gearing that the regulator has assumed would remove a regulatory roadblock to the efficient investment that’s needed to meet the task of decarbonisation.

Extra for experts – a solution

A workable solution could be for the Input Methodologies to accelerate the allowed cash flows in a Net Present Value-neutral manner, as Stephen explains in this short video. The draft Input Methodologies decision canvassed several options to make this happen, of which the most promising was removing indexation of the Regulated Asset Base.

This excerpt was originally published in Vector's stakeholder newsletter.

Frontier Economics' recently advised a number of clients in relation to the Queensland Competition Authority's review of its approach to climate change related expenditure. Below are some highlights and commentary on our advice included in the final position paper.

The Queensland Competition Authority (QCA) has released its final position paper for the Climate Change Expenditure Review 2023, referencing our independent advice to Dalrymple Bay Infrastructure (DBI) and Aurizon Network.

The QCA initiated this review to:

- ensure its framework for assessing the prudency and efficiency of climate change related expenditure is fit-for-purpose and capable of incentivising timely investment when such expenditure would promote the long-term interests of consumers; and

- provide greater clarity and certainty to stakeholders—including consumers and regulated businesses—on how the QCA intends to assess future proposals related to climate adaptation and mitigation expenditure.

Economic regulators need to perform a difficult balancing act when assessing expenditure proposals related to managing climate change risks. The impact of climate change on regulated infrastructure (and, therefore, on users of that infrastructure) is fraught with uncertainty.

- If regulators set a low threshold for the prudency of climate change related expenditure, then consumers may pay more than the efficient amount required to manage climate change risks effectively.

- Conversely, if regulators are too conservative in their assessment of climate change related expenditure, that may imperil the reliability and safety of the infrastructure used to deliver regulated services. This, in turn, may expose consumers to significant economic losses.

Uncertainty over whether regulators will approve climate change related expenditure—or over whether recovery of such expenditure would be disallowed once it has been incurred—may deter regulated businesses from making prudent and efficient investments to improve the resilience of their networks.

Clear guidance about how proposals for climate change related expenditure will be assessed by regulators can help reduce this uncertainty and encourage prudent and efficient investments that may otherwise be foregone.

For this reason, other economic regulators, should conduct their own reviews and publish formal guidelines on how they intend to assess regulatory proposals for climate change related expenditure. The QCA’s guidelines are not specific to any particular industry or jurisdiction, so would be a relevant starting point for other regulators and regulated businesses beyond Queensland.

Managing climate uncertainty to invest prudently and efficiently in resilience

Of the many issues covered by the QCA’s review, our advice focussed on the development of a framework to assess the prudency and efficiency of climate change adaptation expenditure.

Below are some highlights:

We advised Aurizon Network that:

“In assessing prudent and efficient ex ante resilience expenditure the QCA should encourage regulated entities to pragmatically incorporate the uncertainty inherent in climate change related risks into their proposals for adaptation expenditure.”

In our report to DBI, we added:

“Climate-resilience should be a necessary condition to project prudency and efficiency. Investing in infrastructure that is vulnerable, by design, to an accepted range of climate-related risks is likely to be lower cost in the short term but higher cost in total over the life of the asset.”

We discussed the development of an upfront expenditure framework that could facilitate investment under uncertainty, providing advantages to both regulated infrastructure providers and their customers. That is, a framework which:

- is ex-ante in nature;

- relies on the justification for the proposed expenditure;

- includes in its ex-post review mechanisms a consideration of uncertainties related to climate-related risk; and

- is proactive in managing long-term demand uncertainty.

We considered that these elements together would promote regulatory certainty and facilitate investment in prudent and efficient levels of infrastructure resilience.

The Coal Effect – funding and financing approaches to address residual stranding risk

Fossil fuel exposed firms are exposed to transition risk, or risks arising from the process of adjusting towards a lower-carbon economy. This can impact forecasted demand, the value of assets and liabilities, and thereby the risk profile and viability of the regulated business.

A key driver of transition risk for coal exposed companies is policy change. Net zero targets, can reduce domestic demand for coal. However, targets vary in status, development and expected achievement date. This uncertainty, in combination with uncertainty around technological development and carbon abatement costs, makes future demand for coal similarly unclear.

We identified a scenario where Aurizon Network may support more adaptation expenditure to increase the resilience of the network (with the expenditure to go into the regulatory asset base). However, future customers may be unwilling or unable to continue to pay for past adaptation expenditure. These factors create asset stranding risk, which may disincentivise a regulated business from investing in network resilience today, even if the investments are supported by current customers.

We then considered options the QCA might adopt to address asset stranding risk. We discussed the merits of addressing an increased stranding risk associated with climate change via an uplift to the allowed rate of return (i.e., the ‘fair bet’ approach) that would be just sufficient to compensate investors for the increase in stranding risk.

Also considered was the use of accelerated depreciation, which has been used by regulators in Western Australia (ERAWA) and New Zealand (the Commerce Commission) to address the stranding risks faced by gas pipelines following the adoption of emissions targets that have shortened the expected economic life of those regulated assets.

In our advice, we recommended that the QCA should confirm clearly that:

- its regulatory framework will continue to provide regulated businesses with a realistic opportunity to recover past prudent and efficient expenditure over the long term;

- regulatory allowances will be set such that climate change related expenditure that is deemed to be prudent and efficient, based on information available at the time, may be recovered over the expected economic life of the assets; and

- the expected economic life of the assets should be reassessed periodically as new information becomes available.

Overall, we identified the benefits in the QCA providing clear upfront guidance on the types of information and evidence it would require from regulated businesses, to demonstrate asset stranding risks and management responses.

This could include the QCA needing to take into consideration a larger range of plausible future scenarios, rather than focusing on just the expected future profile of demand at a given point in time, reflecting the long-term uncertainty faced by the coal industry.

Frontier Economics Pty Ltd is a member of the Frontier Economics network, and is headquartered in Australia with a subsidiary company, Frontier Economics Pte Ltd in Singapore. Our fellow network member, Frontier Economics Ltd, is headquartered in the United Kingdom. The companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered into by any one company do not impose any obligations on other companies in the network. All views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Pty Ltd.

DOWNLOAD FULL PUBLICATION

This bulletin explains why it is essential for regulators in Australia to adopt financeability tests as standard practice whenever they make a regulatory determination, and to take the results of those tests seriously.Financeability tests are used by regulators in the UK to assess whether the revenues they allow a business to earn over a price control period will be sufficient to finance the business’s operations efficiently. These tests act as an early warning against a regulated business becoming financially constrained or insolvent—an outcome that ultimately harms consumers, or taxpayers, who may be called on to rescue a regulated business providing essential public services from collapse.

By contrast, in Australia, regulators have either refused to employ financeability tests or run them but only pay lip service to the results.

A Case Study: The Thames Water ‘financeability’ problem

Thames Water is Britain’s largest water company, providing water and wastewater services to 15 million customers in London and the Thames Valley.

In late June 2023, alarming reports began to circulate that Thames Water was struggling to meet its debt obligations and may be on the brink of collapse. The crisis deepened as the CEO stepped down suddenly following criticisms about the company’s poor environmental performance and record leakage rates, and a new Chair was appointed hastily to regain control of the situation.

The UK Government and the water sector regulator, Ofwat, began drawing up rescue plans for Thames Water amidst fears that the company might become insolvent. The crisis ended when shareholders agreed to inject £750 million of equity capital into the business, to reduce its debt burden.

The media was quick to blame the financing decisions of the company’s private owners for its woes. Previous owners of Thames Water, including Australian bank Macquarie (dubbed the ‘vampire kangaroo’ by some in the British press), were accused of loading the business with excessive debt, while extracting huge dividends, leaving it unable to meet its financial obligations.

The Thames Water debt crisis

Thames Water is one of the most indebted water companies in Britain. At the time of the crisis, it had £16 billion of debt and a gearing ratio (the proportion of its assets that are financed with debt rather than equity) of around 80%. Ofwat noted that Thames Water (and some other companies) had “borrowed too much.”[1] This meant that the company faced large debt repayments.

The situation was worsened by the fact that nearly 60% of Thames Water’s debt was inflation-linked. That is, a significant portion of the interest Thames Water needed to pay was linked to the retail price index (RPI) measure of inflation. The RPI is similar to the consumer price index (CPI). However, it also includes mortgage interest payments, which makes it more sensitive to changes in interest rates. Hence, Thames Water’s interest bill grew significantly as inflation rose sharply over 2022 and 2023.

But the size of Thames Water’s debt obligations is only one part of the equation.

Inflation and the regulator’s revenue limits

As a natural monopoly, the amount of revenue that Thames Water is allowed to earn is capped through periodic price controls by Ofwat.

A part of that revenue allowance is an amount to cover real interest payments. However, to the extent that a company holds inflation-linked debt, its actual interest bill in each year will be the sum of a base (real) rate plus outturn inflation that year.

Ofwat allows the regulatory asset base (RAB) of the businesses to grow each year in line with actual inflation. Recovery of this inflation-indexed RAB, over 50 years or more, provides the business with compensation for the inflation component of its interest costs.

Herein lies a problem: the business is contractually obliged to pay the entire interest bill every year. But, it will take decades to recover through regulated prices the inflation component of that bill. When inflation starts rising, the mismatch between the business’s regulated cash flows in each price control period and its interest obligations widens.

In short, Thames Water faced a perfect storm: a large pile of debt, rapidly rising interest repayments linked to inflation, and regulated revenues that were insufficient to cover these increasing costs. All of this added up to material risk of default on its debt obligations.

UK regulatory financeability tests: an early warning system

Ofwat has a statutory duty to:

“secure that companies...are able (in particular, by securing reasonable returns on their capital) to finance the proper carrying out of their functions.”[2]

If the annual revenue allowance set by Ofwat is insufficient to pay the business’s interest bill or to attract equity finance, the business will be unable to finance its activities properly or invest in assets. In these circumstances, the business would be unable to deliver services of proper quality to consumers.

Moreover, the financial collapse of essential service providers such as water companies, energy networks or communications firms can cause catastrophic disruptions and economic costs to consumers.

Recognising this, Ofwat and other UK regulators with similar financing duties have developed ‘financeability tests.’ These act as an early warning to detect whether the revenue allowances set by the regulator would be insufficient for an efficient business to remain financeable. If the tests show a likely deterioration in financeability, the regulator can adjust revenue allowances to avert the problem.

Ofwat sets revenue allowances based on a ‘benchmark’ business that uses debt to finance 60% of its assets and maintains a BBB+ credit rating.[3]

The purpose of Ofwat’s financeability test is to assess whether the revenue allowances set in this way are in fact sufficient to support that BBB+ rating at the benchmark 60% gearing. It is effectively a test of the internal consistency of the regulatory decision.

Ofwat and Thames Water

Ofwat decided in its 2019 revenue determination for Thames Water that it needed to accelerate the recovery of costs by £125 million in order for a benchmark business in Thames Water’s circumstances to maintain a BBB+ rating at 60% gearing.

Thames Water argued that, even after bringing forward these allowed revenues, a benchmark business with 60% debt finance would be unable to finance the delivery of its statutory obligations or attract the required amount of equity finance. Ofwat did not accept Thames Water’s representations.

Ofwat also performed a separate test of ‘financial resilience’ based on Thames Water’s actual gearing (at the time) of 80%. Ofwat expressed concerns that Thames Water was very highly geared and noted the company should take steps to improve its financial resilience.

Under this two-pronged test:

- Any problem found using the regulator’s benchmark settings is a problem of the regulator’s making and requires a regulatory remedy; and

- Any problem that is due to the actual business departing from the regulatory benchmark is the responsibility of the company and its owners to fix. Consumers should not be expected to pay more for poor financing decisions taken by the business.

Australian regulators seem to prefer a late warning system

Whereas Ofwat and Thames Water differed in their views about whether the regulatory allowance was sufficient to support financeability, there was strong agreement that consideration of financeability is a vital component of regulatory best practice.

By contrast, Australian regulators have been slow to embrace financeability tests. Regulators in Australia fall into three groups:

- Those that perform no financeability test at all;

- Those that perform a test, but invariably conclude that no action is needed regardless of the outcome of that test; and

- Those that perform a test and conclude that action is needed – but not by them.

The Thames Water case provides a timely reminder that even the largest and most well-resourced regulated businesses can face serious risk of insolvency, which can be disastrous for consumers. Properly implemented financeability tests can avoid such outcomes. Therefore, it is important to consider:

- The essential features of a useful financeability test; and

- The right regulatory responses to the outcomes of financeability tests. (Spoiler alert: The right regulatory response is not to always do nothing.)

Features of a good regulatory financeability test

Financeability tests are an essential element of best practice regulation

It is in the long term interests of customers that an efficient provider of essential services is financeable, so that it can provide services desired by customers. This requires that regulated revenues are sufficient for an efficient business to meet its financial obligations as they fall due and to invest what is needed to deliver regulated services.

If regulated businesses cannot provide their services because they are financially constrained or insolvent, then customers or taxpayers will bear the cost. If the regulated business is financially constrained, it may be unable to make the investments needed to provide the level of service today or into the future that customers want. If a regulated business becomes insolvent, then it will likely be taxpayers that step in to ensure the essential services continue to be provided.

This is why financeability tests are a key part of best practice regulation. The purpose of a financeability test is to ensure that the revenue allowance is sufficient for an efficient business to meet its financial obligations over the forthcoming regulatory period.

The test should also allow the regulator to diagnose the source of the problem, so that appropriate corrective action can be taken.

A two-pronged test is needed to determine appropriate action

Financeability problems can arise because:

- The regulatory allowance is too low to support the benchmark financing parameters (gearing and credit rating) that the regulator assumed when setting that allowance; or

- The regulated business has departed from the benchmark financing parameters (e.g., by adopting higher gearing).

The first is a case of internal inconsistency in the regulator’s process and is for the regulator to resolve. The second is a case of risky financing practices and is for the firm and its owners to resolve.

Regulated businesses should be free to depart from the regulatory benchmark if they choose. The business then keeps any benefits, and bears any costs, of such a departure. Neither the regulator nor consumers should be called on to immunise regulated businesses against bad outcomes arising from such decisions.

The Ofwat approach described above involves a two-part test:

- The ‘financeability’ test is performed using the regulator’s benchmark financing parameters. The test provides an indication of whether the regulatory allowance is sufficient to support those parameters.

- The ‘financial resilience’ test is performed using the firm’s actual financing parameters. It assesses whether the firm’s departure from the regulatory benchmark may be causing problems.

A similar two-pronged test is applied by the NSW Independent Pricing and Regulatory Tribunal (IPART).

The source of any financeability concern can be identified more easily by using two separate tests:

- If a regulated business fails IPART’s ‘benchmark’ test, that implies that the revenue allowance is too low to service what the regulator itself considers is the efficient debt obligation; and

- If a regulated business fails IPART’s ‘actual’ test but passes the benchmark test, that implies that the business is not financially resilient due to its own financing choices.

Recent financeability test practices in Australia

There are almost no examples of Australian regulators taking action to address financeability concerns arising from their decisions to set inadequately low revenue allowances. Some regulators perform no test at all, so have no way to detect the existence of a problem. But, many that do perform financeability tests have chosen to take no action, even when the test has clearly identified a financeability problem.

‘Narrating away’ the outcomes of a financeability test

It is important that regulators acknowledge the outcomes of their financeability tests, respond consistently and do not try to apply a narrative that seeks to ‘explain away’ a potential problem.

IPART

The most important financeability metric considered currently by rating agencies for Australian regulated energy and water businesses is the funds from operations to net debt (FFO/Net Debt) ratio

In IPART’s 2020 determination for Sydney Water, the FFO/Net Debt ratio fell below of the minimum 7.0% threshold specified in IPART’s benchmark test in every year of the regulatory period. This suggested strongly a failure of the benchmark test. IPART should have adjusted Sydney Water’s revenue to ensure an efficient, benchmark business could remain financeable.

However, IPART concluded that the failure of the test on the FFO/Net debt ratio did not indicate a problem. This is because, amongst other reasons, that ratio was expected to improve over the regulatory period towards the target ratio (from 6.6% in 2020-21 to 6.8% in 2023-24). However, it would remain below the required threshold in every year.[4]

According to IPART, there was no problem to fix because the failure of the test was forecast to become less severe over time.

Australian Energy Regulator (AER)

In 2022, the AER undertook a major review of its methodology for setting the allowed rate of return for electricity and gas networks. As part of that review, the AER presented a simplified financeability test to assess the impact of its proposed methodology.

The AER’s test used the FFO/Net debt ratio as the sole metric and set a threshold of ≥7.0% for a ‘pass’.

The AER found that the FFO/Net debt ratio for 25% of the businesses fell below the threshold for a pass.

The AER concluded that there was no evidence of a financeability concern (at the industry level) under its proposed rate of return methodology because 75% of the firms appeared to pass the test.

Of course, this ignored the fact that a quarter of the industry had failed the regulator’s own test.[5]

Not adjusting regulatory decisions in response to a failure of the benchmark financeability test and instead narrating away the outcome is as good as having no test at all.

Applying the wrong solution to the problem

The regulatory response to a financeability problem should properly address the underlying cause of the problem. Without addressing the cause, remedial actions may be misdirected, leading to inefficient outcomes.

If the financeability problem was caused by the business taking imprudent or risky financing decisions (e.g., by gearing up more than the benchmark level), it should not fall to consumers to ‘bail out’ the business for those poor decisions. That would impose unnecessary costs on consumers and create poor incentives for the business to avoid bad financing decisions in future.

However, if the financeability problem was caused by the regulatory allowance being set too low for a efficient business to remain financeable, then the regulator, not shareholders, should fix the problem.

IPART has made this distinction clear:

“If the source of the concern is that prices are too low even for a benchmark efficient business, we think the appropriate remedy is to review our pricing decision. In essence, this step would involve correcting a regulatory error. The financeability test could help identify any such error by applying additional information that may not have been available in the building block model used to set prices.

If the source of the concern is that prices are adequate for a benchmark efficient business but too low for the actual business because its owners have been imprudent or inefficient, there are appropriate remedies. The owners could reduce the business’s level of debt by injecting more equity, accept a lower than market rate of return on their equity, or both. It is an important principle that an inefficient business should not be rewarded for its imprudent decisions at the expense of customers.”[6]

The best way to diagnose the source of a financeability problem is to apply a two-pronged test of the sort used by IPART and Ofwat. Because the benchmark test assumes that the regulated business always finances itself efficiently and prudently, the only explanation for a failure of that test would be a regulatory error that requires correction.

Calibrating the financeability tests incorrectly

Even when a test is structured correctly, it will only be useful if it accurately reflects the financial flows of an efficient benchmark business. If the thresholds for passing the test are set unrealistically low, then genuine financeability tests will go undiagnosed and uncorrected.

For example, when running its benchmark test, IPART assumes that businesses faces real, rather than nominal, debt obligations. But, in reality, companies in Australia issue nominal debt and therefore must pay nominal interest expenses.

Assuming that an efficient regulated business faces lower (i.e., real) interest expenses than it in fact does makes IPART’s benchmark test too easy to pass. Hence, the test is prone to ‘false negatives’—i.e., conclusions that there is no financeability problem, when there is one.

Recommendations for improvements to regulatory financeability tests

These examples show that regulators in Australia either do not apply financeability tests at all, or if they do, typically find reasons not to fix a problem identified by their own financeability tests.

The Thames Water example is a reminder that regulated businesses can face serious financeability problems.

Ofwat concluded at the last price control that Thames Water needed an uplift in allowed revenues of £125 million to support an efficient credit rating, at an efficient level of gearing. The crisis that Thames Water faced would probably have been worse than it was, had Ofwat adopted the approach that Australian regulators follow and ignored the results of its own financeability analysis.

Because regulated businesses deliver essential services, it is consumers that suffer if these businesses become insolvent or financially constrained. In the case of insolvency, taxpayers may also be called upon to rescue the business from collapse.

Therefore, regulators in Australia should view financeability tests as an essential part of best practice and incorporate them as a standard feature into their revenue setting processes.

A good framework for regulatory financeability tests should:

- Be able to identify the source of a financeability problem.

If the cause is imprudent or risky financing decisions by the business, it should be left to investors to deal with. However, a failure of a benchmark test indicates that the problem is a regulatory one. In these situations, the regulator should take action to fix the problem, rather than explain it away or shift the onus on shareholders.

A two-pronged test allows regulators to pinpoint the cause of the problem and ensure that tailored action is taken.

- Be specified in such a way that the outcome—i.e., a ‘pass’ or a ‘fail’—can be identified clearly and objectively.

Regulators should take the outcomes of these tests seriously and not dismiss a clear failure of the test by simply assuming that their regulatory decision is adequate.

- Be calibrated in such a way that the tests are realistic and capable of identifying, rather than masking, genuine problems.

To find out more about how we advise on regulatory issues and financeability, pricing reviews, and more, please reach out to our team.

[1] Ofwat, Thames, debt and water sector finance, 24 July 2023. [2] UK Legistation, Water Industry Act 1991, section 2(2A)(c). [3] Ofwat, PR19 determinations: Thames Water final determination, December 2019. [4] IPART, Review of prices for Sydney Water from 1 July 2020, Final Report, June 2020, p 178. [5] AER, Draft rate of return instrument, Explanatory statement, June 2022, p. 24. [6] IPART, Review of our financeability test, Issues paper, May 2018, p. 32

Frontier Economics Pty Ltd is a member of the Frontier Economics network, and is headquartered in Australia with a subsidiary company, Frontier Economics Pte Ltd in Singapore. Our fellow network member, Frontier Economics Ltd, is headquartered in the United Kingdom. The companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered into by any one company do not impose any obligations on other companies in the network. All views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Pty Ltd.

At the International Institute of Communication’s Telecommunications and Media Forum, Sydney 2023 our Economist Warwick Davis joined a panel on competition issues in the sectors and commented on proposed merger reforms in Australia and the United States. He suggested that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC)’s proposed reforms for processes and legal tests for merger clearance will be contentious but seem more likely to produce economic benefits than the proposed changes to merger guidelines in the United States. This note explains the reasons for his view.

Merger reform proposals are a response to increasing market concentration

Competition authorities in many parts of the world are steering the debate on mergers towards sterner enforcement. The recently released details of proposed changes to merger enforcement in Australia and the United States show that competition authorities are on quite different paths to achieve that goal.

In Australia, details of the ACCC’s proposals for merger reform, as provided to Australian Treasury in March 2023, were recently released under Freedom of Information laws.[1]

The US Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (the Agencies) issued new draft merger Guidelines[2] for comment in July 2023. As in Australia, merger guidelines do not have the status of law, but they have been influential in US court merger proceedings.

The proposed changes are different, but they are both reactions to similar concerns – perceived harms from increasing market concentration that have not been prevented by merger laws and/or enforcement practices:

There is growing evidence to support the view that Australian markets are becoming more concentrated…It is important that Australia’s merger regime is effective in preventing increases in concentration before they occur.[3]

and:

[In the United States] Empirical research…has documented rising consolidation, declining competition, and a resulting assortment of economic ills and risks.[4]

Proposed changes to US Merger Guidelines renew emphasis on market concentration

The Agencies’ draft Guidelines have undergone a substantial change in form and substance from earlier versions.[5] The draft Guidelines show the Agencies’ desire to simplify the analysis of mergers that increase concentration or occur in concentrated markets, tied where possible to legal precedent. The FTC Chair has stated the draft Guidelines do not rely on “a formalistic set of theories” but “seek to understand the practical ways that firms compete, exert control, or block rivals”, and offer several ways to analyse transactions.[6]

The draft Guidelines have 13 specific guidelines that address analytical frameworks and specific challenges relating to serial acquisitions (creeping acquisitions in Australian parlance), buyer power in labour markets, platform markets and minority interests. This includes a return (in Guideline 1) to a stricter application of the ‘rebuttal presumption’ of market concentration that was first developed by the Supreme Court in 1961[7], and the introduction (in Guideline 6) of a rebuttable presumption in the case of vertical mergers, where a market share of more than 50% is involved.[8]

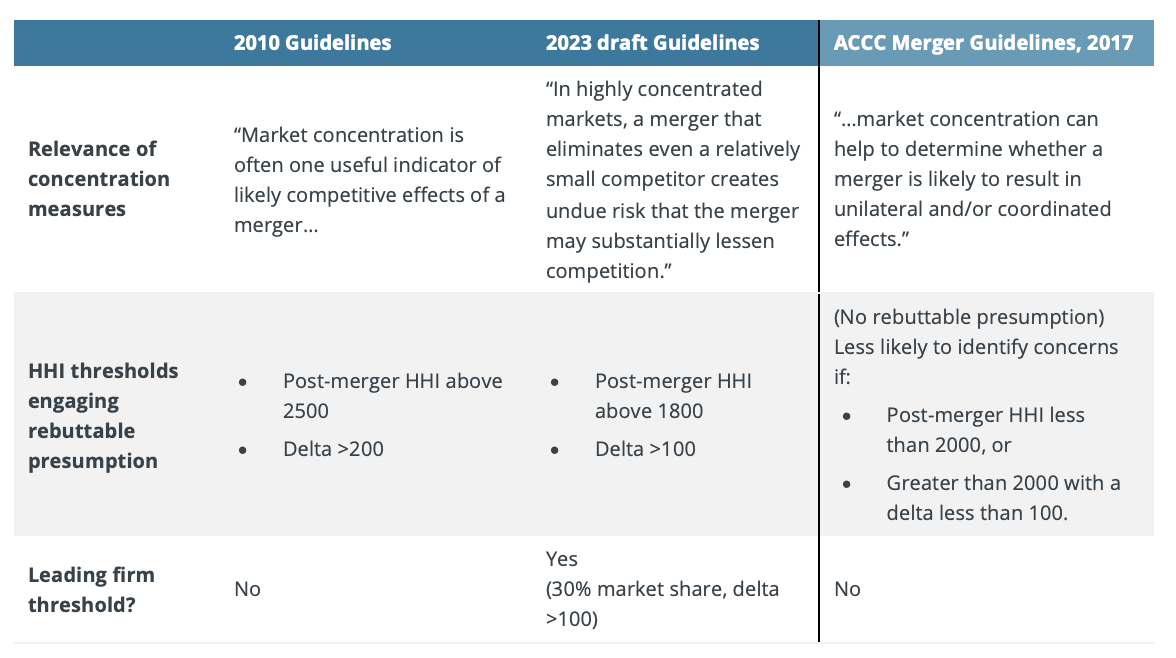

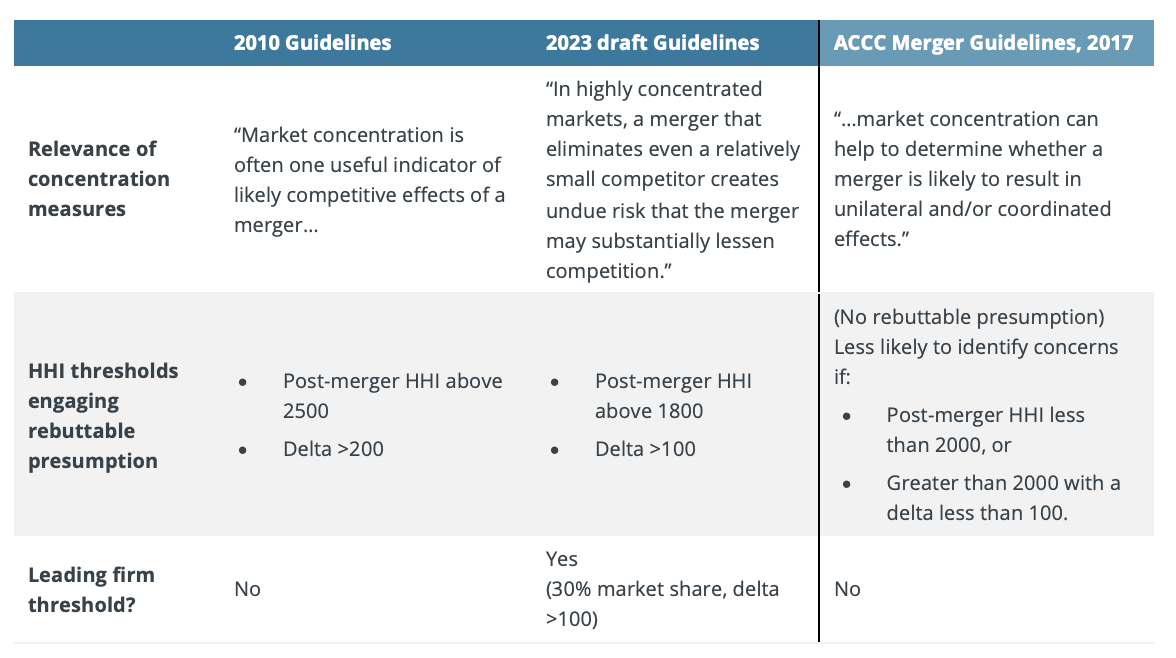

The changes from the 2010 version of the Guidelines on the significance of increasing market concentration are stark, as highlighted in Table 1. The thresholds at which the rebuttable presumption is engaged are reduced: in rough terms, a 6 to 5 merger of equally sized firms would now be subject to the rebuttable presumption while under the 2010 version it would not. For reference, the current ACCC Merger Guidelines approach (2017) is also highlighted, but these thresholds do not create rebuttable presumptions but instead provide an indication of the likelihood of concerns being raised.

Table 1: Changes in treatment of market concentration, US DOJ/FTC Merger Guidelines

Source: US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission, Horizontal Merger Guidelines, August 19, 2010, draft Guidelines, p. 6, ACCC Merger Guidelines, 2017.

Similar problems, but different responses in merger reforms

The ACCC also has expressed concern with increasing market concentration. But the ACCC’s proposed reforms do not specifically focus on elevating market concentration to a more central role in merger analysis. Rather, the key elements of the ACCC’s reform proposals include:

- A formal merger clearance regime: large mergers could not go ahead unless a clearance was obtained from the ACCC or Tribunal.

- Changes to the merger clearance test: mergers can be blocked by the Federal Court under section 50 if they have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition. The ACCC proposes that a merger would be cleared only if the ACCC (or Tribunal, on review) is satisfied that it is not likely to have the effect or likely effect of substantially lessening competition.

- Revisions to the section 50 merger factors: added factors include an emphasis on creeping acquisitions and entrenching existing market power.[9]

Concentrating on the right measure of competition?

We have previously suggested that the ACCC’s proposed changes to the process by which mergers are assessed, including formal merger clearance, are worthy of serious consideration. The changes would address defects in the current informal clearance regime and adjudication processes, particularly by empowering the ACCC to be the principal decision-maker and increasing the transparency of its decisions.

On the added measures, the proposed ACCC reforms are better for not aiming directly at market concentration, albeit that concentration will remain a significant element of merger investigations. This is for two reasons:

- Since the 1970s, economists have grown more sceptical of the causal connections between market concentration, competition, and economic performance. Concentration is only one factor in competitive health, and other market structures and conduct factors can be equally or more important.[10] For example, product differentiation, which is relevant to most mergers in Australia, highlights that the identity of competitors, and the similarity of their products, can have a greater influence on the competitive effects of mergers than aggregate concentration measures.

- So much emphasis on concentration places an undue reliance on the defined markets. The definition of markets is rarely clearcut, particularly where products are differentiated, and is inevitably a matter of judgement.

Striking the right balance on the cost of errors

The ACCC’s proposed changes to the section 50 legal test are likely to have a significant impact on the chance of contentious mergers being proposed and approved. Mergers that have uncertain effects would be more likely to be blocked than under the current system.

One framework through which to view the proposed changes is whether they minimise the total costs of decision-making errors:

- from not blocking anti-competitive mergers, and

- from blocking mergers that pose no threat to competition.

Compared with the existing legal test, the ACCC’s proposed changes will reduce errors of the first kind while increasing errors of the second kind. Both kinds of errors are relevant: while errors of the first kind harm consumers directly, blocking mergers that are pro-competitive will also harm consumers.[11] Undoubtedly, the balance of errors is complex to assess and we expect further debate over whether the proposed change restores or upsets the right balance.

Other proposals to structural merger factors seem more likely to be positive. The proposals focusing on accumulation of market power address long-standing concerns about creeping acquisitions but avoid placing increased weight on market concentration thresholds. This leaves more room for nuance in the merger analysis.

A step in the right direction

The ACCC’s proposals are a serious attempt to improve the processes and outcomes of merger reviews. Although the ACCC may be concerned about market concentration, it is helpful that the ACCC has not looked to tie its proposals directly to that concern – as is being pursued in the United States. While further debate on changes to the legal test is justified, we expect the ACCC’s proposed changes have reasonable prospects of improving competition and economic welfare.

[1] https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/foi_disclosure_documents/ACCC%20FOI%20Request%20100067-2022-2023%20-%20Document%201_0.pdf (ACCC proposals)

[2] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2023/07/ftc-doj-seek-comment-draft-merger-guidelines

[3] ACCC proposals, pp. 4-5.

[4] Remarks of FTC Chair Lina M. Khan, Economic Club of New York, July 24, 2023, p.3.

[5] The Agencies have amended the guidelines several times since the first guidelines were released in 1968, including in 1982, 1984, 1992, 1997, 2010, and 2020.

[6] Remarks of Chair Lina M. Khan, Economic Club of New York, July 24, 2023, p.2.

[7] United States v. Philadelphia Nat. Bank, 374 US 321, 363 (1961).

[8] Draft Guidelines, p. 17: “If the foreclosure share is above 50 percent, that factor alone is a sufficient basis to conclude that the effect of the merger may be to substantially lessen competition, subject to any rebuttal evidence.”

[9] ACCC proposals, p. 11.

[10] For example, in oligopoly settings, common market features such as cost asymmetry between firms or economies of scale can reverse the standard intuition that increasing concentration reduces economic performance.

[11] The ACCC suggests that the increased costs of errors will be borne by the merger parties rather than the public. That would only be true if the merger produced no efficiencies or did not otherwise benefit competition.

Frontier Economics Pty Ltd is a member of the Frontier Economics network, and is headquartered in Australia with a subsidiary company, Frontier Economics Pte Ltd in Singapore. Our fellow network member, Frontier Economics Ltd, is headquartered in the United Kingdom. The companies are independently owned, and legal commitments entered into by any one company do not impose any obligations on other companies in the network. All views expressed in this document are the views of Frontier Economics Pty Ltd.